Varieties of capitalism had been often found …, or invented, depending on one’s standpoint: What some see as difference, as structural rupture is for others not much more than a tiny alteration, not making a real difference. However, one often forgotten question is to ask what capitalism is and in which way it links to Human Rights.

Of course, there is some good reason for painting with a broad brush a picture of antagonism. We may make reference to the definition given by Katarina Pistor, contending

Fundamentally, capital is made from two ingredients: an asset, and the legal code. I use the term “asset” broadly to denote any object, claim, skill, or idea, regardless of its form. In their unadulterated appearance, these simple assets are just that: a piece of dirt, a building, a promise to receive payment at a future date, an idea for a new drug, or a string of digital code. With the right legal coding, any of these assets can be turned into capital and thereby increase its propensity to create wealth for its holder(s).

(Pistor, Katarina, 2019: The Code of Capital. How the Law creates Wealth and Inequality; New Jersey/Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press: 2)

Another definition reads

Here is how capitalism actually works: use a legal framework of private ownership to extract value from the labor of others. The end game is a system that hoards wealth, stifles innovation, and ultimately destroys the value created by cooperation among those who seek to do things that cannot be done alone.”

(Brewer J, 2016: This is How Capitalism Works; https:// artplusmarketing.com/this-is-how-capitalism-actually- works-b2907d1b4d78; 15/09/2

Here, we see that one lives on the cost of somebody else/others – not only with insufficient compensatory transfer, but more in principle without any justification of the appropriation. While we find with primitive accumulation the ‘justification’ of brute force, the justification is now a completely tautological one: ‘Because I define by a legal title something as being owned by me, the ownership establishes the legal title.’

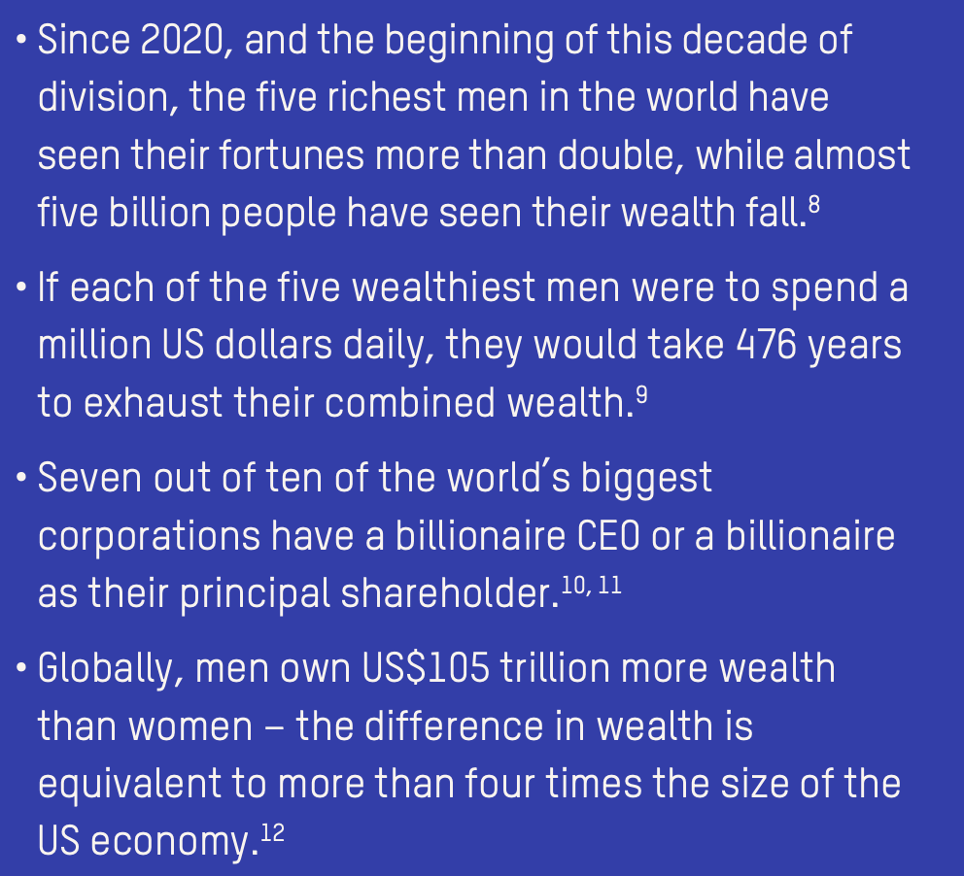

With this, we find these extreme and shocking figures as published earlier this year by OXFAM

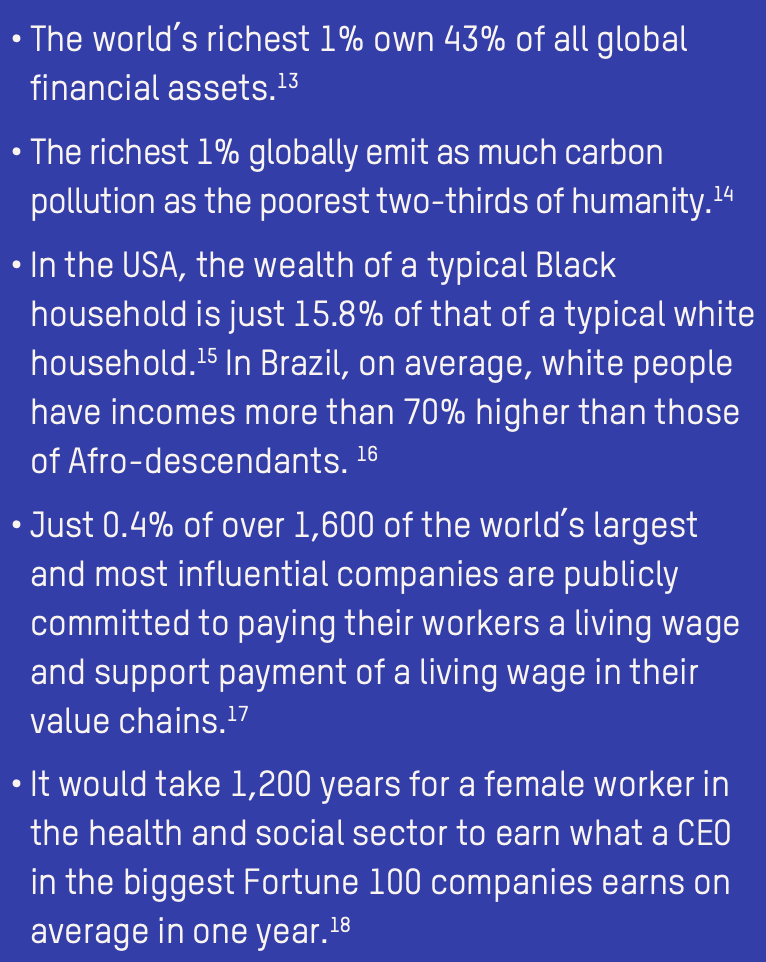

Even more shocking than the inequality is, however, is presumably the other side: origin and costs – part of this shown in the following figures:

(Inequality Inc.; Publication date: 15 January 2024; Authors: Rebecca Riddell, Nabil Ahmed, Alex Maitland, Max Lawson and Anjela Taneja. Contributing authors : Alex Bush, Alexandre Poidatz, Andrew Gogo, Anthony Kamande, Christian Hallum, Gustavo Ferroni, Henry Ushie, Inigo Macias Aymar, Jonas Gielfeldt, , Lies Craeynes, Mariana Anton, Martin Brehm Christensen, Nafkote Dabi, Rachel Noble, Sunil Acharya, Susana Ruiz, Uwe Gneiting and Yaxkin Rodriguez. Commissioning manager: Anjela Taneja; https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/inequality-inc)

It is worthwhile to highlight the massive increase of financial assets. The paradox is that ‘value’ is in fact not generated by productive activities; instead, it is about exploitative processes, in other words the absorption and diversion of monetary values into areas that live by diversion.

In addition to the fall in the rate of profit, a not insignificant, though slightly hidden part, is that the core of production itself is being shifted. Let’s take the simple example of a dining room chair, comparing traditional, handcrafted individual production (a) and modern mass production (b) – here in a rough illustration.

(a) Starting with customisation (dimensions, material …), followed by preparing and setting up the necessary tools and machines, then finally comes the production itself – completed by the “fitting”.

(b) In the second case we have an entirely different setting. Of course, initially we find as well production: the simple production of a chair as in the first case. But now, aiming on mass production, the situation is different because the massification itself is a process that requires main investment, overtaking the initial production. If the product is not completely built in one place, especially if it will be sold for assemblage by the customer him- or herself, the product is – in the taken example – the chair itself and also the suitability for easy mounting. It is about the exact measurement – 100 % equal for every case – and it is about the simplification of the entire process and it’s integration into a wide range of other chairs for dining rooms, equally it should be possible to use the same production method for dining tables of a specific range and also of different models. So, ideally, we find at the end of the day a huge variety of products, at the same time one specific method with a limited number of production processes (or we may say: quasi-universal applicability). In other words, it is the production of one or more pieces of a specific model of a chair, the production of a whole range of models of chairs and the necessary applicability of the same screws, nuts, washers, plugs …, provided tools and so on. The design of this kind of product and production requires a main effort and is increasingly more important for generating value than the process of production in strictu sensu.

In consequence, we find also a redefinition of human beings as socially productive beings: valued is the refined being, detached and alienated from the immediate, i.e. real world. And as much as the Marxist statement

It is not men’s consciousness that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence that determines their consciousness

prevails, as much we find now the existence producing a consciousness that is not able anymore to distinguish right, law and justice. In other words, justice becomes an empty formula that abstracts from fundamentals of existence – existence is now transposed into some weird form of fetishized cocoons, the reality turned upside down – and too often even critique is caught in this thinking: we criticise inequality, but hesitate to name the reasons for it; facing natural catastrophes, we blame climate change, but we forget to emphasise that it are ‘the richest 1 % that are to a large extent behind it; even if this may sound theoretical and detached: it is precisely this constellation that “allows” a CEO to “justify” the privatisation of water: “If people can’t afford it … bad luck.”

In fact, research and negotiations on human rights should not only be concerned with overcoming massive inequality, but above all with combatting an understanding of society that is based in irresponsibility.